I began working for Trinity College of Music London in November of 1986. I was 59 years old then. I had serious misgivings whether I would be able to represent the college in Malaysia. No sooner was I appointed than I realised that there had been so many contenders for the job. Music teachers, music schools and business people had all been trying to get this job. Some of them had even gone to London to meet with the college principal and the board of governors. I was not aware of all this when I was appointed. But when I got cracking on the job, I had to deal with all sorts of people who were much different from my colleagues of teaching days.

I had many things to learn about how the business world operated. It was a ‘dog eat dog’ world out there if one was not careful. Fortunately I had assistance from the college examiners and a few music teachers who came to my aid when I needed them for advice.

In Malaysia, most people were familiar with the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music (ABRSM). The Board was set up to examine students only, whereas Trinity was a music college and teaching institution. Their examinations were conducted in most Commonwealth countries. I had been offered the job in preference to many others who had been vying for the role, because I had teaching experience.

My job was to register students for the examinations and make all the arrangements for the examinations to take place. My wife and I adapted our home to operate as a music studio during exam time. We had always had upright pianos, on which our daughters practised music during their student days. To host the music examinations, we bought a grand piano, which for many years had pride of place in our home. In other towns, we rented studio facilities from the local music schools to hold the Trinity exams. I would collect the visiting examiners from the airport, put them up in a hotel, and transport them around as needed.

I also had a role in making the Trinity qualifications better known among the music schools and teachers. As time went on we also began to promote the spoken English exams as a way for young people to be certified as fluent English language speakers – a valuable qualification at a time when many were concerned about the falling standards of English in Malaysian schools.

In this work I came across some very good music teachers. I had the privilege of meeting English language teachers, music examiners and some excellent music students. I was truly enjoying the job and I was also handsomely paid. My friends and colleagues in Singapore envied what I was doing after retirement from government service in Singapore. And so the years passed.

Eventually, I felt I was getting older and getting tired more easily. Every year the student numbers increased. I was conducting examinations in various towns in Johor and Melaka, driving from place to place in the southern part of peninsular Malaysia. As the only other representative in Malaysia was going to retire, I was expected to take on his responsibilities in Kuala Lumpur as well. By this time I was already 72. I felt I could not carry on any longer as the work entailed some travelling all the time.

There were also many changes going on in the college. New examiners were being appointed and the college itself was being merged with other institutions. I didn’t want to work any longer as the old staff had also left or retired. At the end of 1998 I quit after representing Trinity for 12 and a half years. Some of them, like the chief examiner at Trinity, are still in touch with me to exchange notes of old times. It was good and I had enjoyed working for them. I am now an Anglophile, loving their language, music and culture.

During this time my children successfully completed their studies abroad. Delia had won a cultural exchange scholarship to go to Australia, provided by the American Field Service (AFS). She landed in Tasmania and during her year there finished her Higher School Certificate (HSC) to gain admission in Australian universities. After her exchange year, we decided she should accept a place at the Australian National University in Canberra. She completed an Arts degree and joined The Star newspaper in 1987 as a cadet journalist.

Cynthia was admitted into St Catherine’s School in Sydney in 1982. She began her year 10 studies there as a boarder. Later she completed a course in political science at Sydney University. She pursued her music studies as well and became a Fellow of Trinity College London – its highest qualification in music performance.

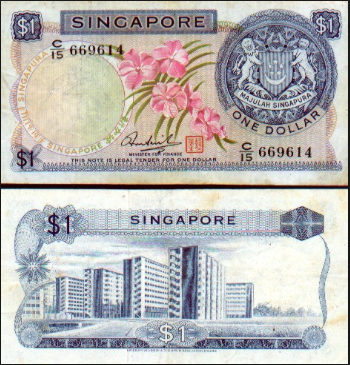

In the case of Benjamin, I had previously admitted him to school in Johor Bahru. This lasted four years, during which I became increasingly unhappy with the standard of education in Malaysia. I took him to finish his last two years of primary schooling at Woodlands Primary School, where I was posted at the time. He did very well and won an ASEAN Scholarship to study at the most prestigious school in Singapore – Raffles Institution. As an ASEAN scholar, he was paid an annual allowance of two thousand Singapore dollars and given other privileges. He did very well in the final examination and decided to study economics. This was a surprise to me as I had planned for him to do engineering and believed that this was also his choice. We wished him well and supported his true choice. He went to the London School of Economics and later graduated with a degree in monetary economics.